James Romm writes a thousand words a day, no more, no less. "I live by the word count tool," he says. "When I get to a thousand I stop, and give the rest of the day to editing and revising what I've already written, or perhaps weeding the garden." It's a disciplined approach that has served the Bard College classicist well across a career spanning biography, narrative history, and translation. But discipline alone doesn't explain what makes Romm's work distinctive; it's his conviction that ancient figures deserve to be seen as flesh and blood rather than marble, complete with all their contradictions and failures.

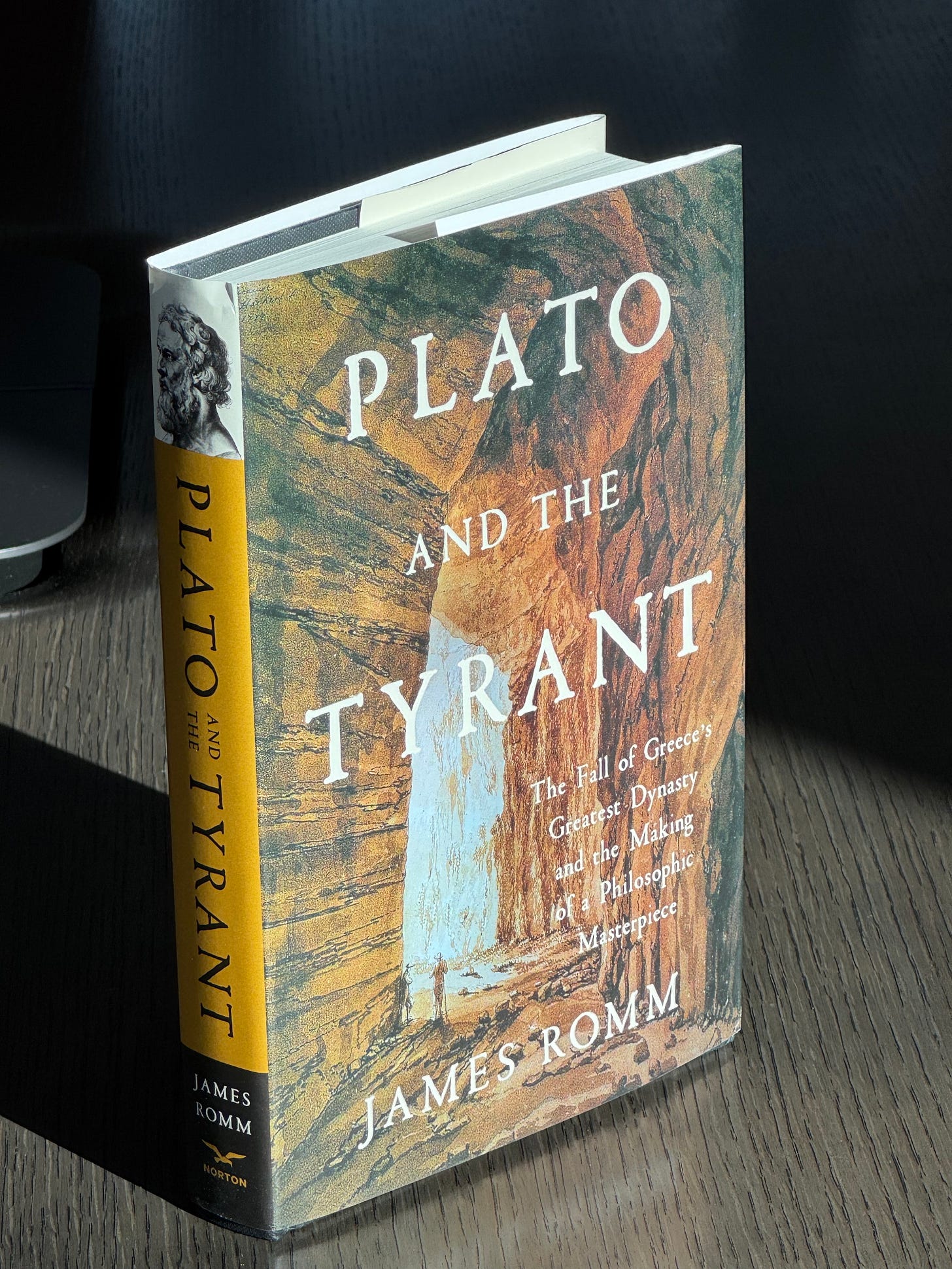

This philosophy animates his latest book, Plato and the Tyrant: The Fall of Greece's Greatest Dynasty and the Making of a Philosophic Masterpiece, which traces the philosopher's entanglement with the autocratic rulers of Syracuse. Far from the timeless sage of the Academy, Romm's Plato emerges as a politically naive idealist whose theories collided headlong with the brutal realities of power. It's a portrait that required Romm to overturn his initial assumptions. "I was wholly bought into Plutarch's very positive view of Dion," he confesses, "and Plato's own self-serving account of his motives in the Syracuse misadventure. It took a while for my skepticism to assert itself."

That skepticism led Romm to some of the most neglected texts in classical literature: the Platonic Letters. "The Platonic Letters totally blew my mind when I began to explore them," he says with unmistakable enthusiasm. "They are the greatest unknown texts from all of Greek antiquity." Long dismissed by scholars as forgeries, these letters, especially the controversial Seventh and Thirteenth, show Plato mired in mundane concerns about money, logistics, and political alliances. The Thirteenth Letter particularly fascinates Romm because it reveals the philosopher working closely with the very tyrants he supposedly disdained. For a scholar drawn to contradiction and complexity, it's irresistible material.

This attraction to flawed greatness runs through all of Romm's work. "I am far more interested in figures with a pronounced mixture of virtues and flaws," he explains. "Seneca makes a compelling study of this kind, as does Demosthenes. So, I guess the failure of noble efforts is the through-line. Failure is so much more interesting than success, as the Greeks understood." It's a perspective that has shaped his approach to Seneca (whose philosophical essays sit oddly beside his blood-soaked tragedies), to the Sacred Band of Thebes (whose military excellence couldn't save them from history's tide), and now to Plato himself.

Romm's research process reflects this commitment to human complexity. As his college librarian can attest, he is "always amassing books." When he finishes a project, "it takes several trips with loaded shopping bags to return everything." But he's equally at home with digital resources, drawing heavily on the Perseus database and the online Loeb Classical Library. The goal is always the same: to find the human being beneath the historical reputation.

This excavatory work often yields surprising discoveries. Asked what most surprised him about Plato, Romm points to "the degree to which he could get his pride hurt. It's clear from the letters he hated to have people question his integrity, even when they had grounds to do so." Such insights emerge from Romm's willingness to take seriously contested sources. While other scholars hedge their bets with asterisks and qualifications, Romm operates by a different principle: "As in a court of law, if evidence is admitted, it should be all the way in; asterisks are the death of good narrative."

That commitment to narrative distinguishes Romm from many of his scholarly colleagues. "Both biographies and narrative histories are, at their root, stories," he insists. It's an approach that occasionally requires leaps of faith. "Very little can be proven absolutely; it's even possible to argue that Plato never went to Sicily at all." But Romm believes the rewards justify the risks. His goal isn't to solve ancient puzzles definitively but to recover the emotional and psychological texture of historical experience.

This methodology proves especially valuable when examining the moral complexities that fascinate Romm. In his previous book on Seneca, he admitted in the preface that he simply didn't know how to judge the philosopher's compromises with Nero. "We can easily condemn him for not separating from Nero, but we can also admire him for trying to keep an autocrat on the right moral path," he reflected. The same ambivalence informs his approach to Plato's Syracusan adventures. Did the philosopher's advisory role legitimize tyranny, or did his efforts represent a noble attempt to reform power from within?

Romm doesn't provide easy answers, but he does illuminate the human stakes. "There are passages of the Republic," he notes, "that ring of self-justification. And in the Laws, he clearly attempts to explain himself to a dubious public." The public had reason for doubt: Plato's interventions in Syracuse ended not in philosophical reform but in exile, rebellion, and political collapse. Yet for Romm, this failure makes Plato more rather than less interesting. The tension between idealistic theory and messy practice left visible scars on the philosopher's later work, evidence of a thinker who dared to test his ideas against reality and paid the price.

This preference for complicated figures over simple heroes reflects Romm's broader approach to the classical world. "We don't deify ancient figures so much as fossilize them," he observes. "When one looks hard at the texts, one finds people made of flesh and blood, not marble." That recovery of the human element drives all his work, whether he's examining Seneca's contradictions (he compared him to "Ralph Waldo Emerson also composing Faust") or tracing the emotional dynamics of ancient political alliances.

The approach seems particularly relevant at a moment when intellectuals again find themselves courted by authoritarian figures. Romm doesn't belabor contemporary parallels, but he sees resonance between Plato's dilemmas and our own. The questions that ancient philosophers faced about power, compromise, and moral responsibility haven't disappeared; they've simply taken new forms.

After decades of scholarship, Romm remains most energized by figures who embody these tensions. His forthcoming biography of Demosthenes promises another study in noble failure. This orator spent his career warning Athens about Philip of Macedon, only to watch his city-state system collapse anyway. It's the kind of story that allows Romm to practice what he preaches: finding the human drama within the historical sweep and discovering that our most instructive guides are often those who dared greatly and fell short. In Romm's telling, such failures illuminate not just the past but the persistent challenges of living an examined life in an unexamined world.

Readers interested in following James Romm can find him on his website and Instagram.

James Romm is the James H. Ottaway Jr. Professor of Classics at Bard College and editor of the Ancient Lives biography series from Yale University Press. He is the author of several other studies of Greek and Roman history, and his reviews and essays appear regularly in the Wall Street Journal and the New York Review of Books.

‘Always amassing books’ is a motto to live by!