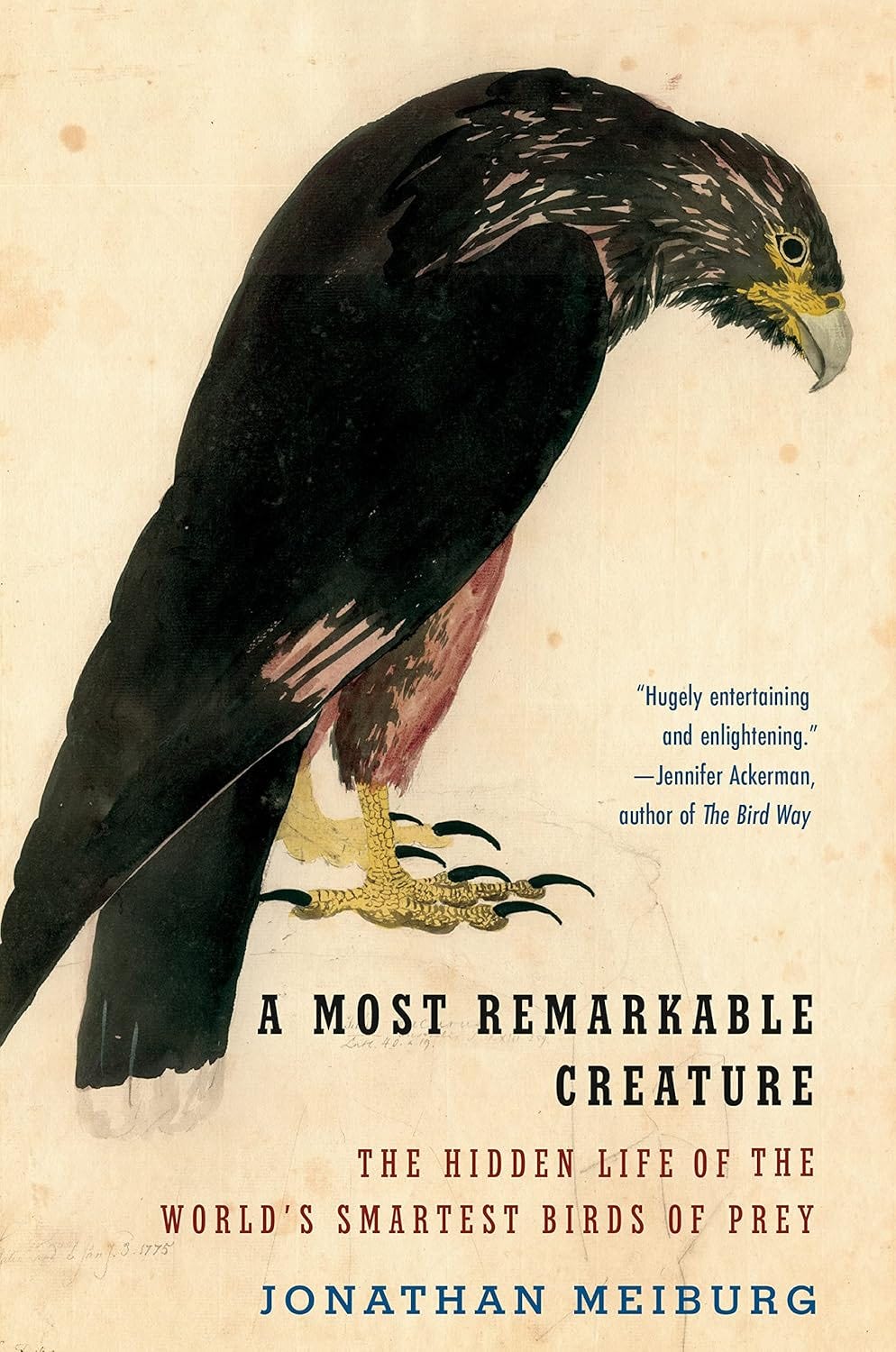

Strange Birds and Kindred Spirits: A Review of Jonathan Meiburg’s "A Most Remarkable Creature"

In A Most Remarkable Creature, Jonathan Meiburg begins with a question about one peculiar bird, the striated caracara of the Falkland Islands, but soon widens his lens to take in the entire caracara family, a group of intelligent, often overlooked birds of prey found across the Americas. The resulting book is a deeply informed and reflective journey that moves through time and across continents, combining natural history, biography, evolutionary science, and personal narrative into an investigation of what it means to live and adapt on a changing planet.

Meiburg is as interested in ideas as he is in animals. With their un-raptor-like behavior, the caracaras question our assumptions about intelligence, instinct, and evolution. He tracks several species, from the social, almost urban chimangos of Argentina to the wasp-hunting red-throats of the Amazon basin and the roadside-scavenging crested caracaras of Florida. Along the way, he digs into their evolutionary past, the ecological pressures that shaped them, and the misfit roles they occupy in human-dominated landscapes.

Running parallel to this exploration is Meiburg's engagement with a lineage of naturalists, thinkers, and explorers who have tried, each in their own way, to see the world on its own terms. He revisits Charles Darwin's early impressions of the Falklands, considers Alfred Russel Wallace's evolutionary insights, and reflects on the strange career of Alexander Skutch, a botanist turned bird obsessive who fled corporate life for Costa Rica. He even invokes figures like Fray José de Acosta, who strained to reconcile New World biodiversity with biblical doctrine. Yet the figure who occupies the most sustained attention is William Henry Hudson, the Anglo-Argentine field naturalist and writer whose work fused scientific observation with philosophical reflection. For Meiburg, Hudson is a companion spirit, a solitary observer shaped by the Pampas and eventually stranded in Edwardian England, where he wrote with deep sensitivity about the kinship between animals and humans. Of Hudson, Meiburg writes, "This was his greatest theme: that only by looking to the nonhuman world, with all the tools of science and art, can we see what we really are—and that we aren't as alone as we feel." This insight becomes something like the book's mission statement, as Meiburg also seeks to transcend the boundaries between scientific inquiry and emotional connection to the living world.

Meiburg's prose is disciplined and lucid, grounded in specific detail. He is at his best when evoking the feel of a place, from the Falkland Islands' blasted ridges to Guyana's riverine forests. Yet this is not travel writing in any conventional sense. Meiburg refuses to reduce landscapes to postcard imagery; instead, he renders them as complex ecological theaters where natural history unfolds. The book's emotional tone leans toward wonder, laced with a quiet sorrow. Losses past and future haunt the narrative, whether it's the extinction of the warrah, the erasure of Hudson's legacy, or the shrinking frontiers for species whose flexibility may no longer be enough.

A Most Remarkable Creature is not an argument for policy, but for attention. It doesn't offer solutions so much as a reframing of the problem: what might we learn from the creatures we tend to ignore, those neither glamorous nor doomed, but simply strange, persistent, and adaptable? Meiburg's achievement is to render the familiar unfamiliar and ask us to look again, not just at the birds, but at the assumptions shaping how we value the natural world.

Like the caracara, the book is unpretentious yet remarkably adaptive, confidently moving between scientific exposition, biographical portrait, and philosophical reflection. This is a rare book: deeply researched, emotionally resonant without sentimentality, and intellectually ambitious while remaining accessible. It joins the ranks of modern nature writing that doesn't just describe the world but questions how we know it.

Thank you for this lovely review! I read the book almost immediately after it was first published. It was delightful -- and as you said, a call for attention.