When Danish author Jane Mondrup talks about speculative fiction, she doesn't frame it as an escape from reality. On the contrary, for her, the genre is one of the most honest ways to reflect the world as it is. "Our imagination can do anything, so why limit it to something that seems realistic?" she asks. "In a way, I see the weird and speculative genres as more reflective of the world like it is."

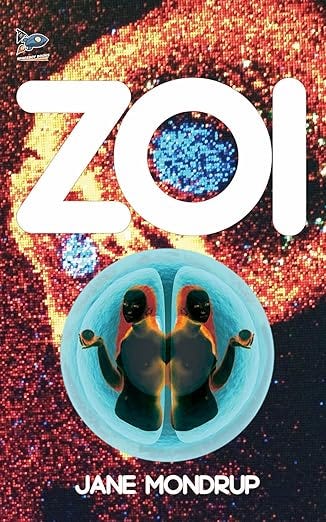

Her latest novel, Zoi, is a sustained interrogation of what it means to remain human when the boundaries of biology, identity, and consciousness are not merely challenged but rewritten. Set within a sentient, space-dwelling lifeform—a "zoi"—the book is part first-contact narrative, part philosophical meditation, and explores territory that few science fiction novels have dared to attempt.

Mondrup, whose 2019 debut, Zeitgeist, fused alternate history, mythology, and philosophical intrigue, draws on an eclectic blend of disciplines for Zoi. At its scientific heart lies the theory of symbiogenesis: the process by which complex eukaryotic cells are thought to have evolved when one organism was absorbed into another and became an organelle. The idea first came to her via a podcast about this theory, the episode Cellmates from Radiolab. "What appealed to me," she recalls, "was the concept of one life form becoming part of another, but still retaining some individuality."

From this biological premise emerged a story of remarkable originality. In Zoi, humanity encounters a series of vast, spacefaring life forms that not only survive in interstellar space but also invite human integration. "The zoi possesses a system designed to help foreign organisms survive," Mondrup explains. "It's the opposite of an immune defense."

This radical hospitality becomes both the novel's premise and its philosophical engine. The protagonist, Amira, is a xenobiologist who joins a crew sent to study a zoi from within. What begins as exploration quickly becomes transformation. As the zoi learns to sustain and even replicate its human visitors, Amira and her colleagues must reckon with the dissolution of bodily autonomy, the emergence of doppelgängers, and the terrifying intimacy of shared biology.

For Mondrup, these speculative conceits are not flights of fancy; they are extensions of existing scientific thought. But her priority remains emotional authenticity. "Sometimes you just have to drop an idea," she admits, "but if you instead work on making it more emotionally persuasive... it often gets even more inventive."

Indeed, Zoi never loses sight of the human stakes within its grand biological canvas. Mondrup is keenly aware of how physical transformation parallels psychological change. "We are our bodies," she states. "Some decisions and choices are easy, some are very difficult, and some are impossible to make. The zois influence the hormonal systems of its inhabitants, and this steers them towards certain behaviors. To the protagonist, Amira, the fight to stay somewhat in control is important, but she has to compromise, like we all do."

Despite the book's evident philosophical ambitions, Mondrup is no slave to abstraction. Her approach to craft is pragmatic, even collaborative. "I start from a rough outline and let the story evolve," she says. "But I won't know if something works before I write it." Revision, too, is an iterative and community-driven process. "I write a few chapters at a time and have my writing group critique them. Having someone put their finger on the problematic elements does not hamper my creativity. On the contrary, it helps me navigate the writing process."

Community is clearly central to her identity as a writer. Although she writes in solitude, Mondrup describes the Scandinavian SFF scene, with its blend of writers, readers, and academics, as an egalitarian space that has had a profound influence on her growth. "That kind of equality really appeals to me," she notes.

This balance between the cerebral and the communal, between speculative scale and human specificity, is what makes Zoi so distinctive. There is an undercurrent of horror in the novel, particularly in its treatment of bodily change and the blurring of self and other, that Mondrup embraces with characteristic nuance. "I'm kind of squeamish when it comes to very explicit horror," she laughs, "but I love the way the genre treats even the most uncomfortable subjects. What interests me is taking this discomfort in new directions, harnessing it without necessarily ending in a terrible conclusion."

The result is a novel that resists conventional endings and easy interpretations. The zoi's replication of its human guests, creating functional but eerily distinct copies, poses existential questions about continuity, memory, and identity. "One person becomes two, and both have the same memories up to the point of separation," Mondrup explains. "If you had another version of yourself, would it be your soulmate, or would you oppose each other? A bit of both would be my guess."

Though some early readers have likened Zoi to Stanisław Lem's Solaris, Mondrup sees the comparison as partial. "Zoi is in a way an accidental First Contact story," she says. "The inspiration from Earth biology means that I had a very concrete model for my aliens in the eukaryotic cell. I hope I found some ideas that are new—though you never know if someone thought of it before, and I just didn't come across their work."

Influences aside, Mondrup's literary voice is her own, that's equally at home with Ursula K. Le Guin's sociological curiosity, Octavia Butler's visceral intensity, and Ted Chiang's contemplative elegance. In Zoi, she merges scientific rigor with emotional truth, producing a narrative that is both unsettling and intellectually resonant.

Zoi ultimately suggests that transformation, biological, psychological, existential, might not just be inevitable but also desirable. Mondrup's work dares to ask not only what is alien, but whether we ourselves might become alien, willingly, irrevocably, and perhaps joyfully.

Readers interested in following Jane Mondrup can find her on her website, Facebook, and Instagram.