In the quiet reading rooms of the British Library,

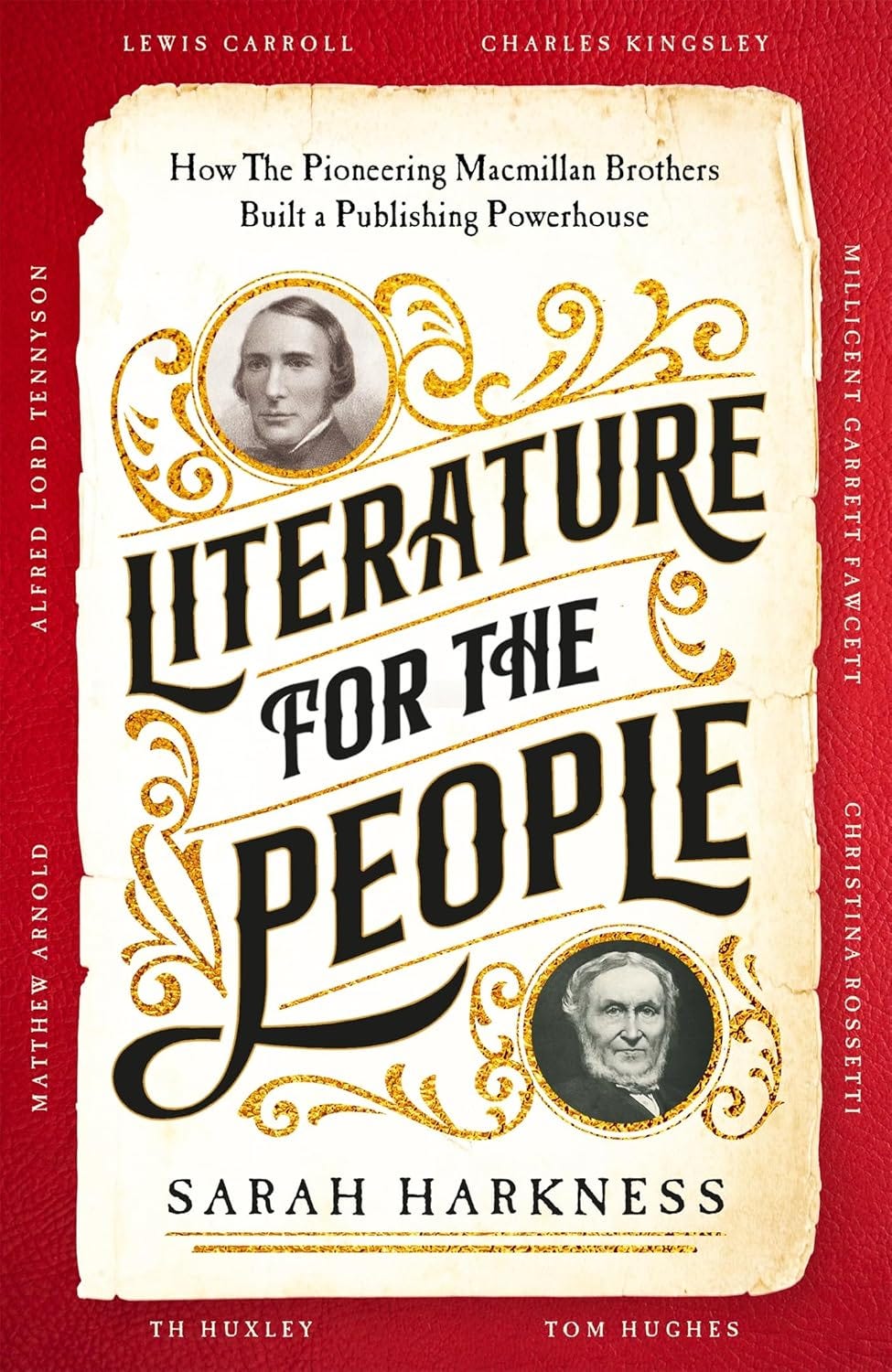

found herself immersed in thousands of handwritten letters from Victorian publishers Daniel and Alexander Macmillan. This meticulous research, conducted over years, would eventually culminate in her biography Literature for the People. Yet just two decades earlier, Harkness had been navigating the very different world of corporate finance, with no inkling that she would one day become a celebrated biographer of overlooked historical figures.An Unexpected Literary Path

"I never expected to be an author," Harkness admits, reflecting on her transition from executive to writer. "But after my full-time career came to an end, twenty years ago, I had the leisure to pursue some private research interests, and I quickly found so much material, that putting it into a book seemed logical—and then I discovered how much I liked to write!" This discovery, while fulfilling, didn't immediately translate to publishing success. The path from personal research to published author involved years of refining her craft and overcoming obstacles, including one particularly motivating setback.

"A very blunt literary agent told me that I didn't have the credentials to write a biography—and it made me mad," Harkness recalls with a hint of the determination that would later serve her well. Rather than abandoning her literary ambitions, she channeled this frustration into action, pursuing an MA in Biography at the University of Buckingham under the tutelage of Professor Jane Ridley, whose work she admired. The academic validation proved transformative. "Getting a Distinction in my MA gave me so much confidence in what I was doing, and that even if my writing style wasn't the most formal or academic, it was still an acceptable way of telling the story. I definitely discovered that I was a story-teller!"

Corporate Skills in a Creative Context

Harkness's breakthrough came when she won The Tony Lothian Prize for her uncommissioned biography Literature for the People, a recognition that changed everything. "It was absolutely crucial—winning the prize meant that I was signed up by an extremely well-respected literary agent within 24 hours. A huge boost!" With this literary validation, Harkness found that her previous career, far from irrelevant to her new pursuit, provided an unexpected foundation for biographical writing. "I spent a lot of time in my first career writing prospectuses, which taught me about attention to detail and the basic rules of good prose, summarizing, editing and refining," she explains. These skills transferred directly to the meticulous research required for historical biography, where she would need to sift through and organize original primary sources efficiently.

This corporate background also gave her unique insight into her subjects' worlds. When writing about the Macmillan brothers and their publishing enterprise, Harkness notes, "I think it was important to remember that I was writing about two men who launched a business, so I had an understanding of the rules of commerce—balance sheets, debt, cashflow and profits, all things that the Macmillans had to worry about as well."

Biography as Living History

For Harkness, historical biography serves a unique purpose in understanding the past. "Biography is my favourite sort of history. I'm fascinated by people, personality, behaviour," she explains, highlighting how individual stories can illuminate broader historical contexts. "I think telling the story through the focus of one particular character really helps the reader to get a grip on what is going on," she adds. For example, in her work on the Macmillan brothers, the personal struggles of Daniel, including the heartbreaking loss of his first love, provide a human lens through which readers can understand the larger Victorian publishing landscape. Reading the letters detailing this personal tragedy gave her "a completely different understanding of what was driving him on, and made him so human".

The Research Detective

Harkness approaches her research with both pragmatism and scholarly rigor. "Start with Wikipedia!" she advises with refreshing candor. "The best way of getting the signposts and bare bones I need." From there, however, she dives deep into primary sources, where the fundamental discoveries happen. "I try to get to as many original, primary sources as possible, manuscripts, diaries, letters," she explains. "Reading thousands of letters in Daniel and Alexander Macmillan's handwriting was time-consuming but critical—it meant that what I was writing about them was original and true, and it helped me to understand their characters." For the Macmillans and their circle, she spent countless hours at the British Library examining these materials firsthand.

Sometimes, however, the historical record presents challenges rather than revelations. With her earlier subject, artist Nelly Erichsen, Harkness faced the opposite problem: "almost no original material at all. I even discovered that some quite substantial archives of her letters and diaries had been 'lost' or disposed of at some point, which was heartbreaking." Rather than abandoning the project, she transformed these gaps into meaningful exploration. "I was still determined to try to piece her story together, but where there were gaping holes—such as 'what did she actually look like', or 'why did she never marry?', I used those questions to inspire some text, some speculation, and it fitted with my thesis that far too many talented women have been completely forgotten."

Crafting Historical Narratives

The organization of vast amounts of research material presents its challenges. "I work really hard at filing stuff!" Harkness says. "I have box files for hard copies, divided by subject, and my OneDrive is full of folders and sub-folders." During her work on the Macmillan biography, she tried to "match box-files to proposed chapters," which helped manage the chronology of information.

One of the most challenging aspects of biographical writing is determining which details to include. "The closer you get to a subject, the more the details, and the background, become lodged in your mind, and it's hard to work out how much of this information the average reader will already know," she explains. Harkness strikes a balance by trying to "signpost any big chunks of background information, so that a well-informed reader might be able to skip..." She tries to be selective about her research findings, avoiding the inclusion of material solely because she discovered it "unless it has genuine shock or surprise value, or sometimes just because I thought it was funny." She recognizes that she goes down "a lot of rabbit holes" and tries to be "ruthless" about what makes it into the final narrative.

Making historical figures relatable to contemporary readers requires finding universal touchpoints. "You need to find something in their life that is not limited by the age in which they lived—how they felt about their wife or their son, for instance—all emotions we can relate to today," Harkness says. "They are human, after all." When handling controversial aspects of her subjects' lives, Harkness approaches with empathy rather than judgment. "I had to think very carefully about this when I was researching the Macmillan family and came across some quite shocking new information which had never been disclosed before," she reveals. "I have no wish to be sensationalist, or to judge. I'm generally a sympathetic person, and I try to write as if the family were in the room with me, but without hiding the facts. And don't speculate, or if you do, be very clear". She mentioned speculating about figures like Fanny Macmillan and her daughter Kate, making it clear that it was speculation.

Impact and Future Horizons

Harkness's research has unearthed significant historical revelations, particularly regarding the Macmillan family. "It has to be that two of the women in the family killed themselves, and no one had ever said," she shares. "I made the connection through death certificates and newspaper cuttings, it was a huge and tragic discovery." The finding has broader historical significance, as "these two women were the grandmother and aunt of British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, and he never talked about it. But in 1930 he had a nervous breakdown, which was partly public knowledge: his very domineering American mother had him shipped off to a Swiss sanatorium to recover - I think she would have been truly scared that suicidal tendencies might be inherited".

Looking to the future, Harkness is drawn to more recent historical periods and women's experiences. "I'd like to write about women, and about a period closer to my own time. I'm particularly interested in my mother's generation—women born in the early decades of the 20th century, who had the vote, had an education, but still had to fight if they wanted an interesting career, particularly if they married. And they went through WW2—I'm interested in how these experiences inspired some of them to break down barriers. I have some in mind!" This generation, who lived through World War II and subsequent societal changes, represents the bridge between historical constraints and modern opportunities.

For aspiring biographers, particularly those interested in lesser-known figures, Harkness offers practical advice born of experience. "It's very hard to get a publisher interested in an unknown person. Pointing out that they will stay unknown if no-one publishes the book doesn't work!" she notes with characteristic directness. "So you need to be ruthlessly focused on WHY we need to know about this person—and secondly about why YOU are the person to tell the story."

A Legacy of Rediscovery

Through meticulous archival detective work and a storyteller's sensibility, Harkness resurrects voices that history nearly forgot. Her revelations, from the Macmillan family's hidden tragedies to Nelly Erichsen's artistic legacy, don't merely uncover historical facts; they transform how we understand both the Victorian era and our own. As she turns her attention to the pioneering women of the early 20th century, Harkness brings the same forensic attention to archival gaps that once concealed family tragedies and forgotten artists. Through her work, these historical silences become as revealing as the documents themselves, each absence an invitation to recover what might otherwise be permanently lost to collective memory.

Such a good interview, and Sarah Harkness is so inspiring as a biographer (as well as very nice.)

As usual, extremely well-written. I love an author who goes to the primary texts! It's surprising how few actually do.